Introduction

The last time we looked at this (https://tamiyabase.com/articles/53-how-to/230-neutralising-alkaline-battery-leaks-with-lemon-juice) I suggested using lemon juice to neutralise the remains from leaked alkaline batteries in RC transmitters and the like.

It’s definitely better than scraping the terminals with a knife or wet & dry paper, and is likely to be found at home or your nearest supermarket, but straight citric acid – the active ingredient in lemon juice – is much more effective.

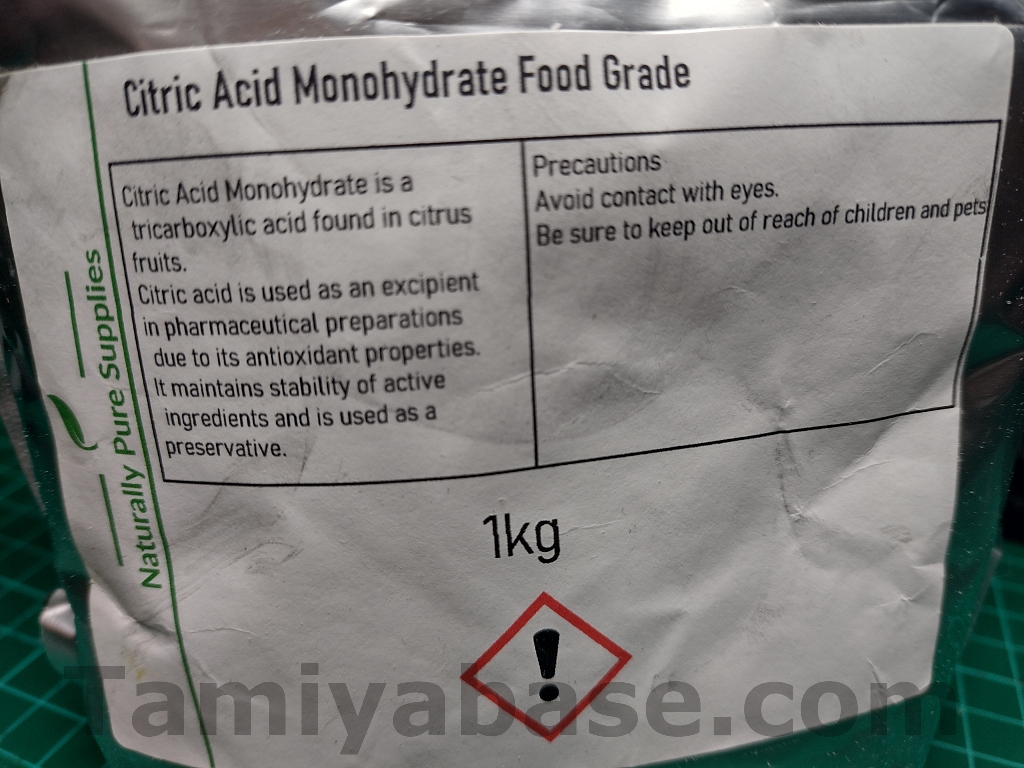

You may be able to get it from a chemist/pharmacy (you should look for Anhydrous Food Grade powder or granules) as other legitimate uses include descaling, food preserving and making DIY bath fizzes, but it’s more likely you’ll need to get it mail order. I know that can be a faff – and most of the cost is going to be in the shipping weight – but you should be able to find 500g (or even 1Kg) packs, posted, for less than 7 GBP (at the time of writing, autumn 2023).

Safety Warning

The pH of citric acid is at a maximum around 2.2 (which compares to around 2.7 for lemon juice) so it’s still a weak acid, and although it can be bought (in the UK at least) for home use with no restrictions, it still makes sense to handle it with care (gloves and eye protection), keep the powder secure from youngsters, and to dispose of used solution carefully (down the sink with plenty of water to flush).

The Theory

This works because alkaline batteries use an alkaline (or “basic”, if you prefer) electrolyte with a pH of 10 to 11, so using an acid will neutralise the residue created when they leak, leaving your battery contacts closer to neutral (pH 7).

Zinc Chloride batteries (which are unlikely to be found in RC equipment TBH, as they were only ever suitable for low drain applications, and even then when you couldn’t afford “proper” alkaline cells BITD) are mildly acidic, so this method isn’t going to work on residue leaked from them.

It will work on Ni-Cd battery leaks though, as they are also alkaline.

Method

The example shown here is an Acoms AP-227 transmitter where I used a fibreglass pencil to remove enough blue/green corrosion to make it function, but it’s really not as good as I’d like. I’m almost certain it’s not the same one as shown in the earlier article ;) .

Do what you can to minimise the area that’s going to get wet, and make it as easy to handle as is practical. On some transmitters you may be able to unplug the wiring for the battery contacts from the circuit board once you’ve opened the case.

On the Acoms AP-227 (“mk.i”) here, although most of the affected parts are held on back of the case that separates completely, two on the contacts are permanently attached to the PCB, and the board is attached to the rest of the unit by several wires.

I can’t recommend unsoldering them, but if you undo just one internal screw, the board will swing loose enough that you can dunk the contacts – and not too much else – in a shallow depth of citric acid solution.

Find a suitable container: 1 litre plastic takeaway containers are excellent, or thick plastic bags in good condition (so you’re sure they’re not going to leak) can be a volume saving alternative once you’ve applied tape strategically.

Mix a strong solution* (like 20g per 500ml of water), it helps the crystals dissolve, and the solution is more effective if the solution is warm, say around 50c which is about halfway between body temperature and as hot as water should be coming out of a domestic tap.

* Less is more? I hadn’t really quantified the measurements when I did this the first couple of times, it was a case of “about yea much” grams of crystals to “that looks about right” ml of water. This time I weighed out 30g (just over an ounce) of citric acid before adding 600ml of water from the hot tap, and carefully stirring to dissolve the small amount or crystal that hadn’t already dissolved. This was possibly a little more than was actually needed, and the reaction was a little faster than it needed to be, so I’ve adjusted the ratio, above.

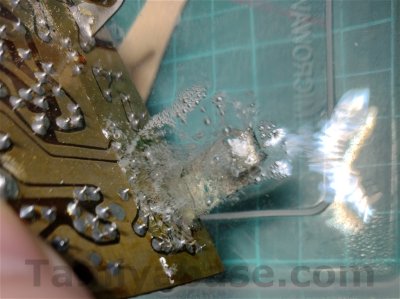

Pour on and observe the fizzing (apologies for the out of focus thumb, the reaction starts very quickly). It’s unlikely you’ll use up all the acid in the solution, so if the reaction stops, there’s nothing left to neutralise. In practice I don’t think I’d let it go quite that far – where battery residue has got between the copper and the nickel plating, dissolving that residue will cause the plating to come off, and that may well happen over a much larger area than in needs too. I’d keep an eye on the worst areas of the contacts, and once those look clean, stop.

Carefully rinse off under the tap, and dry the parts. Shaking them off and air drying them in a warm place is probably good enough, but I like to accelerate the process with a hairdryer. Make sure everything is properly dry before reassembly, and definitely before using the item again.

Carefully dispose of the used solution. In the small quantities we're likely to be using in RC, it’s fine to go down the regular mains connected drain - especially if you rinse away with plenty of clean water.

pH Tests

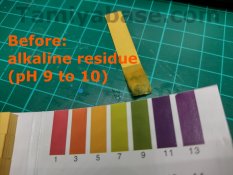

I dug out my universal pH indicator paper, wetted a bit of the contacts & wicked up a sample – this showed a pH of 9 or even 10 in places. That’s about as strong as the human digestive tract can deal with, and is typically found in over the counter reflux treatments, and high electrolyte post-exercise drinks.

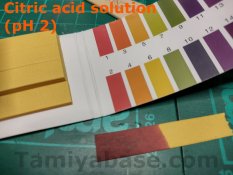

I also tested my citric acid solution – that had a pH of around 2, maybe as low as 1.5. That’s probably more than it needed to be – see the note * above.

However, for comparison, gastric acid is around pH 1, and while it’s unpleasant to be upchucked on and you might even be worried about whether it’s infectious, I don’t think anyone would worry that it was actually going to injure you, psyche notwithstanding ;)

After cleaning, I tested the same area of contacts again and found the pH wasn’t quite back up to 7 (neutral), that probably means I wasn’t quite as thorough in rinsing as I should have been. Another test after a more careful rinse & scrub showed things were back to neutral.

Conclusion

I’ve found this method much more effective than using lemon juice – though it does come at the cost of slightly more difficulty getting the citric acid crystals in the first place, and requires more caution in use, storage and disposal.

However, whereas lemon juice only worked on a relatively fresh leak, this time I was able to improve a previously inadequate cleaning attempt too. I’ve also used it on the remains of decades old, previously untouched leaks, and the results are even better.

In future, I’ll be using the citric acid for dealing with this sort of thing, and will be keeping the lemon juice strictly for pancakes.

__________________________

Written by TB member Jonny Retro